The Hidden History of the Contact Sheet

Introduction

A contact sheet is a direct contact print of a whole roll or set of negatives: tiny, 1:1 frames arranged in a grid so photographers and editors can review, compare, and choose which images to enlarge. More than a proof, it’s an editing map and an archive artifact that reveals approach, pacing, and near-misses alongside the “hero” frame. In the 20th century darkroom, the contact sheet was the first moment of truth; in the archive, it’s often the most candid record of a photographer’s thinking.

TL;DR: the contact sheet is where seeing turns into selecting and history gets made (or crossed out).

Early Origins

Before enlargers were practical, most 19th-century prints were made by contact: a negative pressed against sensitized paper, exposed by sunlight, then developed. Albumen and other slow printing-out papers favored contact work; only later did solar and then electric enlargers make big prints routine. The idea of enlarging existed early (Talbot proposed it; Woodward’s 1857 solar enlarger made it usable), but for decades contact printing was the norm, especially with large glass negatives.

A window into that era: Atget’s workroom shows multiple contact printing frames wooden, glass-clamped devices used to keep negative and paper tightly aligned for sharp contact prints.

Rise of 35mm and Photojournalism

The Leica I (public launch in 1925) and 35mm roll film unlocked fast, handheld shooting and the narrative rhythm of frame-to-frame exploration. With dozens of exposures per roll, the contact sheet became essential: a compact storyboard for sequencing and selection in newsrooms and agencies. Leica’s small camera helped define reportage and street photography for figures like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, and cemented 35mm as the global standard.

The golden age of print media ran on contact sheets. Weekly picture magazines most famously LIFE (1936–1972) built photo essays from rolls: editors, researchers, and layout teams worked over contact sheets, trading notes, narrowing choices, and crafting narrative arcs. Recent museum exhibitions draw directly from LIFE’s archives contact sheets, assignment outlines, and layout mocks to illustrate how pictures became stories.

Marked-up Sheets as Creative Dialogue

If the grid shows everything, the marks show intention. Photographers and editors used grease pencil/china marker ticks, circles, and crops to isolate frames, test sequences, and debate choices. In the Magnum tradition, those layers of wax lines are a visible record of editing an “intimate glimpse into the working process,” as the Magnum Contact Sheets project puts it. Museums and archives note these annotations explicitly; for instance, Diane Arbus contact sheets in The Met include frames marked with yellow wax pencil and handwritten notes.

The result is a conversation on paper: photographer intent vs. editorial needs, aesthetics vs. narrative clarity. Even government photographers worked this way public-domain White House proof sheets often show selection slashes and frame numbers that speak to how images entered (or missed) the historical record.

Transition to Digital

Digital workflows reproduced the contact sheet’s function even as the medium changed. Adobe Lightroom and Adobe Bridge made grid-based culling and PDF/JPEG contact sheets one click away, while Photo Mechanic became the industry’s ultra-fast ingest/caption/cull tool for working photojournalists. The sheet may be virtual now, but the logic see everything, pick ruthlessly, annotate context persists.

And so

Why does the contact sheet still grab us? Because it tells the whole story not just the iconic frame, but the approach, the misfires, the instincts, the edits. It’s humility and craft in one artifact: proof that great photographs are discovered as much as they are made. Whether you’re flipping a brittle 8×10 from the archive or skimming a digital grid, the contact sheet invites you back into the moment where choice becomes authorship.

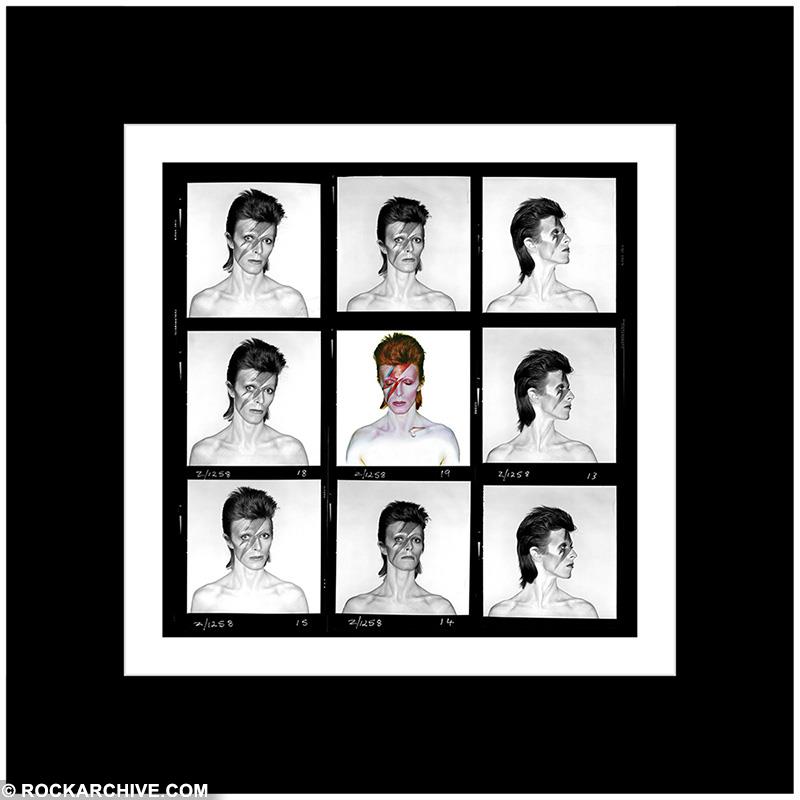

Image Credits

-

Cover & example of editorial markings: Reagan White House contact sheet (Public Domain).

https://www.rockarchive.com/media/1891/david-bowie-db002duffy.jpg?width=800&height=800&mode=stretch&overlay=watermark.png&overlay.size=230,20&overlay.position=0,780 -

Atget’s work room with contact printing frames (The Met, CC0):

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/-Atget%27s_Work_Room_with_Contact_Printing_Frames-_MET_DP112720.jpg -

Leica 1 Model A (1925) (Wikimedia Commons, JPG):

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e5/Leica_1_model_A_%286659021655%29.jpg -

Generic 35mm contact sheet (CC BY-SA):

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ad/B%26W_35mm_Film_Contact_Sheet._Surrey_UK.jpg -

Nancy Wong contact sheet, 1980 (CC BY-SA 4.0):

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/24/Contact_sheet_Nancy_Wong_1980.jpg

Sources & Further Reading

- Definition & darkroom practice of contact prints; 19th-century prevalence.

- History of enlargers from solar to electric; why contact printing dominated early on.

- Leica I introduction (1925) and its impact on reportage/photojournalism.

- LIFE magazine’s editorial workflow & the role of contact sheets.

- Magnum Contact Sheets and the value of grease-pencil annotations.

- Museum record of Diane Arbus contact sheets with wax-pencil markings.

- Lightroom contact sheet/print module and Photo Mechanic’s ingest/culling role.