A Brief, Noisy History of New York Through Its Photographers

By Sambit Biswas

A Brief, Noisy History of New York Through Its Photographers

Introduction

New York has always been a city that looks back at you. It stares from plate glass and puddles, from subway windows and deli cases, and since the late 19th centuryfrom photographs that tried, in their own ways, to argue with the city's noise. What follows is a brisk walk through that argument: who made it, what they saw, and how their pictures kept changing the terms.

TL;DR: New York photographers didn't just document the city they argued with it, and those arguments shaped how we see urban life itself.

Reformers with magnesium flash (1890s–1910s)

The modern story starts in darkness tenements with no light and less air until Jacob Riis arrived with a suitcase of gear and a moral agenda. How the Other Half Lives (1890) used flash powder and blunt captions to shock middle class readers; the book didn't just sell it helped force housing reform and put "tenement" on the nation's conscience.

Photo by Jacob Riis

Lewis Hine, a teacher with a sociologist's patience, followed with photographs that made policy feel personal: Ellis Island portraits; child laborers with lint in their hair and adulthood in their eyes. Hine's images, commissioned by the National Child Labor Committee, are widely credited with moving public opinion and eventually the law.

Photo by Lewis Hine

The city as an architectural character (1930s)

If Riis and Hine insisted the city notice its people, Berenice Abbott insisted we notice the city itself. Back from Paris and inspired by Atget, she spent 1935–1939 mapping New York's growing bones for the WPA: Changing New York, a project that turned skylines, storefronts, and scaffolding into a civic selfportrait just as modernity hardened into steel.

Photo by Berenice Abbott

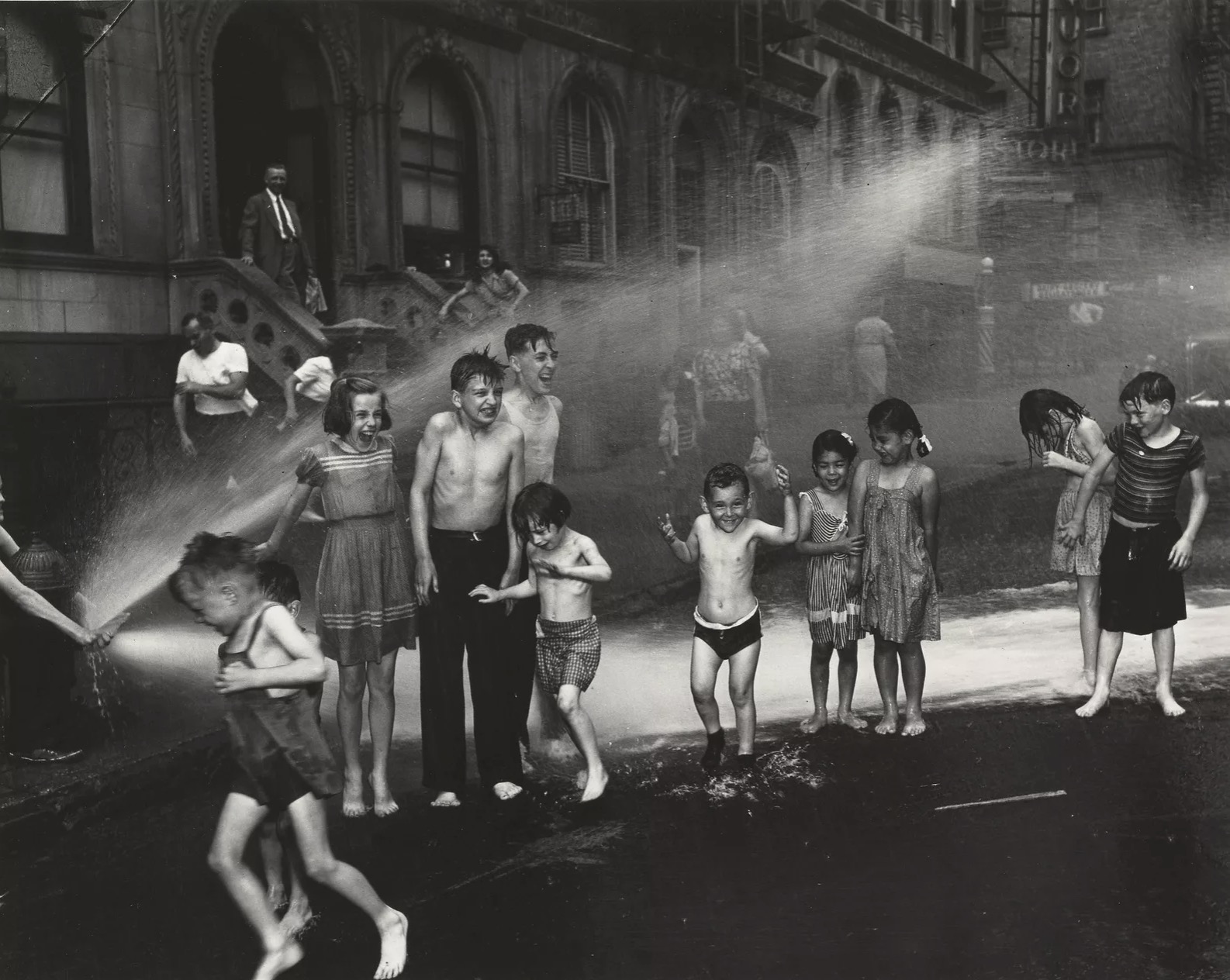

At the same time, the Photo League a cooperative of New York photographers and organizers treated the street as a seminar on democracy. Their classes, critiques, and assignments fused craft with conscience; the League's blacklisting during the Red Scare dissolved the group in 1951, but its pedagogy and pictures outlived the smear.

Flashbulbs, chalk drawings, and tabloid noir (1930s–50s)

On the night beat, Weegee (Arthur Fellig) made crime scenes and crowds feel operatic sirens, steam, sequins, all jammed into the same negative. His 1945 book Naked City helped fix a myth of New York that still refuses to retire.

Photo by Weegee (Arthur Fellig)

A few blocks and several temperaments away, Helen Levitt pointed a small camera at sidewalk theater especially children who took the street as their stage. Her work is central to how we read "street photography" today: unsentimental, improvisational, fleet.

The mid century crank of the dial (1950s–60s)

If you want to see a book blow the doors off a genre, try William Klein's Life Is Good & Good for You in New York (1956): wilfully messy, gloriously kinetic, and at the time heretical. It remains a touchstone for how to photograph a city that refuses to stand still.

Around the same moment, Diane Arbus trained her lens on the charged space between how people present themselves and how the world sees them pictures that made "street" feel less like a location and more like an ethical encounter.

Garry Winogrand widened the frame to the city's entire metabolism tilted horizons, feral timing, joy bordering on panic. His New York pictures from the '60s are practically a humidity index for public life.

And then there was Saul Leiter, who stayed local (East 10th Street) and looked slantwise: rain smeared windows, muted reds, a city glimpsed between umbrellas proof that New York could whisper in color decades before the canon said it could.

Harlem's register and the poetry of tone (1950s–70s)

No survey of New York is honest without Roy DeCarava, whose low key prints about everyday Harlem life (and music) changed how blackness and the city were rendered on the page; his book with Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, sings with ordinary grace.

A generation later, Dawoud Bey's Harlem, U.S.A. (shot 1975–78; first shown at the Studio Museum in 1979) offered posed, respectful portraits that let neighbors author their own presence.

Meanwhile, Gordon Parks already LIFE magazine's first Black staff photographer made "Harlem Gang Leader" (1948), a landmark essay that shows how editorial choices can shape, and sometimes distort, a community's image even as they bring it national attention.

Underground color, uptown style (1970s–80s)

Bruce Davidson's Subway (1986) is a humid opera of graffiti, neon, menace, and tenderness proof that the train is both a stage and a mirror.

Photo by Bruce Davidson

On the surface, Bill Cunningham pedaled the most democratic beat in town street fashion as anthropology. His "On the Street" column for The New York Times made an institution out of simply paying attention.

Photo by Bill Cunningham

In Brooklyn and the Bronx, Jamel Shabazz built a studio out of sidewalks, documenting B-boy stance, friendship, and style in the years hiphop learned how to dress.

And because New York never limited "street" to one culture, Martha Cooper (with Henry Chalfant) published Subway Art (1984), the field guide that introduced the city's graffiti to the world.

Photo by Martha Cooper

Downtown, Nan Goldin turned her circle into a living archive the slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency which has since become one of the city's most argued over love letters.

Why this lineage still matters

Across a century, New York photographers kept renegotiating what "public" means. Reformers used pictures as leverage; modernists made the skyline sentient; tabloid poets and sidewalk lyricists redefined candor; Harlem's artists insisted on tonal dignity; the subway and the street became laboratories for style, survival, and community. Each era borrowed the same raw material crowds, corners, weather and made a new sentence out of it.

If you're building your own syllabus, start with these short primers that map the terrain: James Maher's historical overview of social photography in New York, and Christie's capsule tour of post war street heavyweights. They're efficient doors into a very large room.

Sources & Further Reading

- Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (Library of Congress resources)

- Lewis Hine's child-labor work (ICP archive)

- Berenice Abbott's Changing New York (NYPL collection)

- The Photo League's legacy (The Jewish Museum's The Radical Camera)

- Weegee's Naked City (Britannica)

- Helen Levitt essays (MoMA / New Yorker)

- William Klein's New York photobook (Aperture)

- Roy DeCarava & Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (David Zwirner)

- Dawoud Bey's Harlem, U.S.A. (Studio Museum, Yale Books)

- Bruce Davidson's Subway (Aperture)

- Jamel Shabazz's Back in the Days

- Martha Cooper & Henry Chalfant, Subway Art

- Nan Goldin's Ballad (MoMA)

- James Maher's historical overview of social photography in New York

- Christie's capsule tour of post-war street heavyweights